CROSSROADS: ARCHITECTURAL REMNANTS AND FUTURES IN UZBEKISTAN

︎ Typology: Research

︎ Location: Multiple locations, Uzbekistan

I intend to travel across Uzbekistan over the course of a month to document how the country’s history of overlapping cultural influences reflects in its architecture. I will find and document sites of layered architectural histories, exposing the effects of thousands of years of conquest and occupation on the country’s urban fabric. My research will explore the incongruities between Uzbekistan’s ancient history, its Soviet period, and the country’s future. Uzbekistan’s relative youth as an independent country is ushering in a new era of architectural agency. What is being built? What is being replaced?

For millennia, the mountains, steppes, and deserts that lie inside the borders of modern Uzbekistan have been sites of monumental cultural exchange. Its central status along the Silk Road trade routes cemented its value to foreign and domestic rulers. In western Uzbekistan, the Ferghana Valley was Alexander the Great’s northernmost conquest. In the south, the ancient region of Bactria became a point of contact between Zoroastrian, Hellenic, and Buddhist cultures. Islamic Turkic and Persian dynasties transformed the already thriving cities of Samarkand and Bukhara into preeminent centers of science in the medieval Muslim world.

The cultural mixtures that happened along the routes of the old Silk Road brought a range of architectural styles into the region of Uzbekistan. The ephemeral architecture of the steppes used by nomadic Mongol conquerors contrasts heavily with the ornately decorated (and monumental) madrasahs, mosques, and minarets of the medieval Islamic rulers. Residential architectures across Uzbekistan reflected the intense continental climates. Houses in Bukhara shielded residents from the city’s dust and noise, while in Khiva, terraces and courtyards allowed for increased airflow, allowing residents to control the heat of the Kyzylkum desert.

By the late 19th century, the Russian Empire took control of Uzbekistan. The 1917 Bolshevik Revolution established the Uzbek Soviet Socialist Republic, and under Soviet governance, the region rapidly modernized, industrialized, and urbanized. Tashkent was chosen in 1930 as the capital of the newly formed Uzbek SSR and exploded in population during World War II as a result of factory relocations and Stalin’s forced deportation programs. Tashkent’s historic city was largely demolished in 1966 by an earthquake, prompting its restoration and reconstruction into a model Soviet city. In other parts of the country, Soviet-styled peripheries were erected around ancient city centers, creating an incredible dichotomy of modernity and antiquity.

The Soviets had to navigate Uzbekistan’s over 6500-year history when urbanizing the region’s cities. Secular policies enabled the destruction of many mosques, and fresh memories of the Russian Empire’s brutal feudal past hampered early preservation attempts. In the 1960s, a new attitude towards cultural heritage was born. Historical areas were demarcated in cities like Samarkand and Bukhara, and construction was undergone to restore the region’s once magnificent monuments. Visions for tourism in the area focused on presenting an idealized image of “the Silk Road,” erasing vast amounts of historic architecture.

Now, 30 years after the collapse of the USSR, the same socialist neighborhoods that replaced the historic dwellings of Uzbekistan are falling into disrepair. Historical city centers are still protected, thriving as a result of a burgeoning tourist economy. A desire on the part of the current government to distance itself from the USSR has brought forth the erasure of Soviet architecture across the country. The post-Soviet reincorporation of Islam into Uzbek culture has borne a new architecture for the country, one that echoes the neo-Islamic styles of the Persian Gulf petro-states.

My research trip will focus on the following themes:

BREAKING WITH THE PAST: A ONCE NEW, SOCIALIST UZBEKISTAN

My research will begin in Tashkent, the nation’s capital, where many Soviet-built cultural sites remain. Tashkent is a very modern city, transformed by contemporary real estate development, making it a crucial location for my research. In addition to the documentation of governmental and cultural buildings in the center of the city, I plan to explore residential neighborhoods to record modern habitation of Soviet-era apartments and commercial buildings.

DAMPENED INFLUENCES: RURAL DENSITIES IN FERGHANA

Using Uzbekistan’s robust rail network, I will travel east to the Ferghana Valley to study the country’s industrial and agricultural centers. Research will be conducted in Ferghana and Kokand: two smaller cities with lower rates of contemporary development. Throughout the valley, Khanate-era palaces contrast with traditional Tsarist architecture. I will return to Tashkent by rail to continue my journey across the country.

REDISCOVERING ISLAMIC ARCHITECTURE: PRESERVATION, IDENTITY, TOURISM

After my time in eastern Uzbekistan, I will travel west to the Silk Road cities of Samarkand, Bukhara, and Khiva. All three are listed as UNESCO World Heritage sites for their impressively preserved historic quarters. These cities will allow me to document the interactions taking place between the modern peripheral urbanizations of Uzbekistan and the ancient desert trade hubs. I will be visiting numerous historical sites across the three cities to supplement my understanding of the region’s millennia-old history.

20TH CENTURY QUINQUENNIAL PLANS: INDUSTRIAL DEVELOPMENT IN THE ARAL SEA

Last on the itinerary will be Nukus, the sixth-largest city in Uzbekistan and is the center of western Uzbekistan’s Karakalpakstan region. The remote town was founded in 1932, and many examples of Soviet vernacular architecture remain. Nukus is home to the Savitsky Museum, the second most extensive collection of Russian Avant-Garde art.

From Nukus, I will take a day trip to Moynak before returning to Tashkent to depart. Moynak was on the shores of the Aral Sea but collapsed after the environmental catastrophe that led to the water’s complete evaporation. The town is a shell of its former self, with countless examples of decaying Soviet-era buildings.

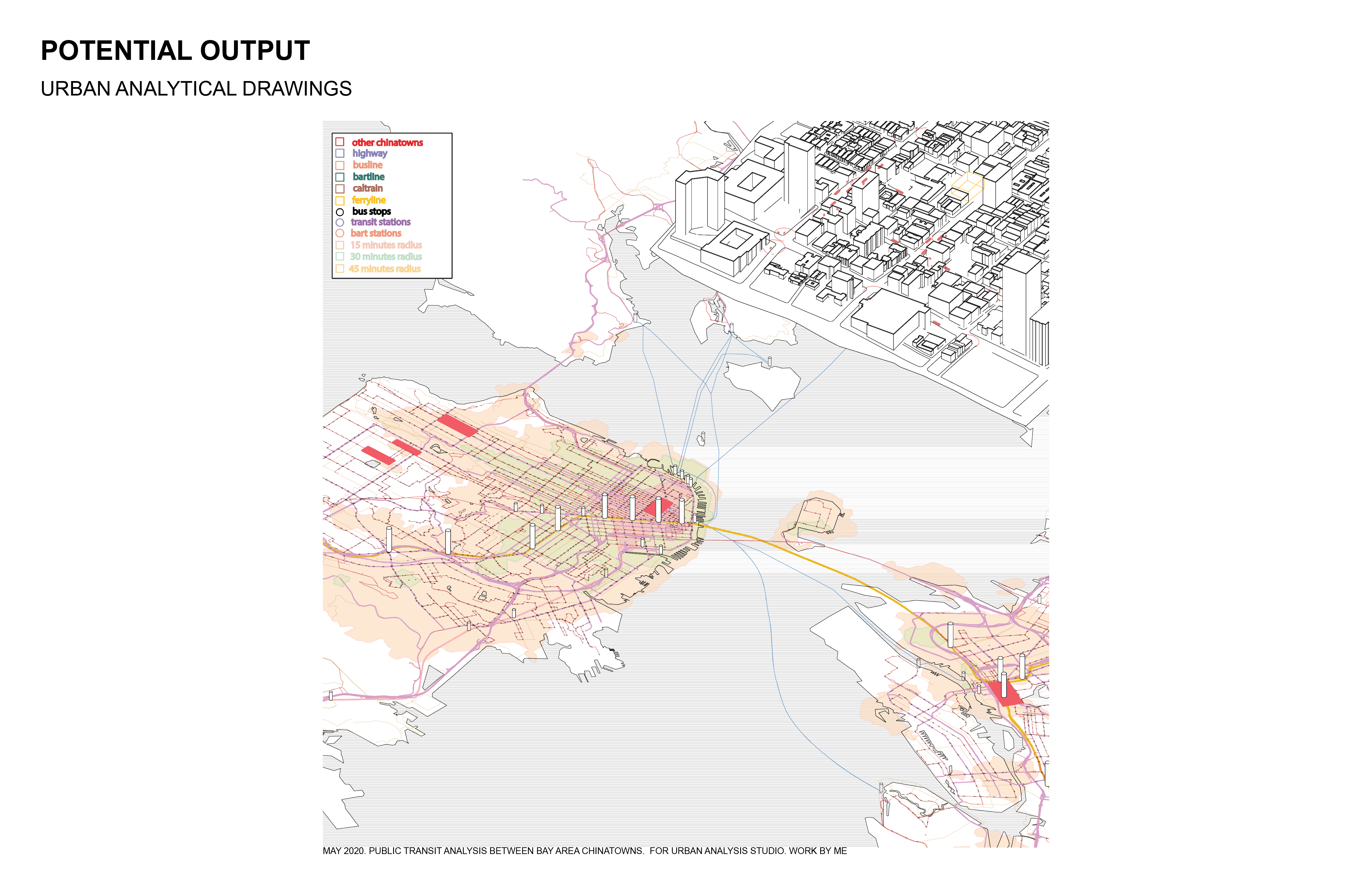

Upon returning to the United States, I will synthesize the sketches, maps, diagrams, and photographs done on site to create a series of analytical drawings documenting the changing urban landscape of Uzbekistan. My research in Uzbekistan will reveal explicit and implicit sites of architectural overlaps in both the buildings and urban fabric of the cities visited. The high resolution analytical drawings and maps will bring the impact of Uzbekistan’s history on its architecture to a broader audience. Uzbekistan has been at the crossroads of history for thousands of years and its architecture will reflect that.

︎ Typology: Research

︎ Location: Multiple locations, Uzbekistan

I intend to travel across Uzbekistan over the course of a month to document how the country’s history of overlapping cultural influences reflects in its architecture. I will find and document sites of layered architectural histories, exposing the effects of thousands of years of conquest and occupation on the country’s urban fabric. My research will explore the incongruities between Uzbekistan’s ancient history, its Soviet period, and the country’s future. Uzbekistan’s relative youth as an independent country is ushering in a new era of architectural agency. What is being built? What is being replaced?

For millennia, the mountains, steppes, and deserts that lie inside the borders of modern Uzbekistan have been sites of monumental cultural exchange. Its central status along the Silk Road trade routes cemented its value to foreign and domestic rulers. In western Uzbekistan, the Ferghana Valley was Alexander the Great’s northernmost conquest. In the south, the ancient region of Bactria became a point of contact between Zoroastrian, Hellenic, and Buddhist cultures. Islamic Turkic and Persian dynasties transformed the already thriving cities of Samarkand and Bukhara into preeminent centers of science in the medieval Muslim world.

The cultural mixtures that happened along the routes of the old Silk Road brought a range of architectural styles into the region of Uzbekistan. The ephemeral architecture of the steppes used by nomadic Mongol conquerors contrasts heavily with the ornately decorated (and monumental) madrasahs, mosques, and minarets of the medieval Islamic rulers. Residential architectures across Uzbekistan reflected the intense continental climates. Houses in Bukhara shielded residents from the city’s dust and noise, while in Khiva, terraces and courtyards allowed for increased airflow, allowing residents to control the heat of the Kyzylkum desert.

By the late 19th century, the Russian Empire took control of Uzbekistan. The 1917 Bolshevik Revolution established the Uzbek Soviet Socialist Republic, and under Soviet governance, the region rapidly modernized, industrialized, and urbanized. Tashkent was chosen in 1930 as the capital of the newly formed Uzbek SSR and exploded in population during World War II as a result of factory relocations and Stalin’s forced deportation programs. Tashkent’s historic city was largely demolished in 1966 by an earthquake, prompting its restoration and reconstruction into a model Soviet city. In other parts of the country, Soviet-styled peripheries were erected around ancient city centers, creating an incredible dichotomy of modernity and antiquity.

The Soviets had to navigate Uzbekistan’s over 6500-year history when urbanizing the region’s cities. Secular policies enabled the destruction of many mosques, and fresh memories of the Russian Empire’s brutal feudal past hampered early preservation attempts. In the 1960s, a new attitude towards cultural heritage was born. Historical areas were demarcated in cities like Samarkand and Bukhara, and construction was undergone to restore the region’s once magnificent monuments. Visions for tourism in the area focused on presenting an idealized image of “the Silk Road,” erasing vast amounts of historic architecture.

Now, 30 years after the collapse of the USSR, the same socialist neighborhoods that replaced the historic dwellings of Uzbekistan are falling into disrepair. Historical city centers are still protected, thriving as a result of a burgeoning tourist economy. A desire on the part of the current government to distance itself from the USSR has brought forth the erasure of Soviet architecture across the country. The post-Soviet reincorporation of Islam into Uzbek culture has borne a new architecture for the country, one that echoes the neo-Islamic styles of the Persian Gulf petro-states.

My research trip will focus on the following themes:

BREAKING WITH THE PAST: A ONCE NEW, SOCIALIST UZBEKISTAN

My research will begin in Tashkent, the nation’s capital, where many Soviet-built cultural sites remain. Tashkent is a very modern city, transformed by contemporary real estate development, making it a crucial location for my research. In addition to the documentation of governmental and cultural buildings in the center of the city, I plan to explore residential neighborhoods to record modern habitation of Soviet-era apartments and commercial buildings.

DAMPENED INFLUENCES: RURAL DENSITIES IN FERGHANA

Using Uzbekistan’s robust rail network, I will travel east to the Ferghana Valley to study the country’s industrial and agricultural centers. Research will be conducted in Ferghana and Kokand: two smaller cities with lower rates of contemporary development. Throughout the valley, Khanate-era palaces contrast with traditional Tsarist architecture. I will return to Tashkent by rail to continue my journey across the country.

REDISCOVERING ISLAMIC ARCHITECTURE: PRESERVATION, IDENTITY, TOURISM

After my time in eastern Uzbekistan, I will travel west to the Silk Road cities of Samarkand, Bukhara, and Khiva. All three are listed as UNESCO World Heritage sites for their impressively preserved historic quarters. These cities will allow me to document the interactions taking place between the modern peripheral urbanizations of Uzbekistan and the ancient desert trade hubs. I will be visiting numerous historical sites across the three cities to supplement my understanding of the region’s millennia-old history.

20TH CENTURY QUINQUENNIAL PLANS: INDUSTRIAL DEVELOPMENT IN THE ARAL SEA

Last on the itinerary will be Nukus, the sixth-largest city in Uzbekistan and is the center of western Uzbekistan’s Karakalpakstan region. The remote town was founded in 1932, and many examples of Soviet vernacular architecture remain. Nukus is home to the Savitsky Museum, the second most extensive collection of Russian Avant-Garde art.

From Nukus, I will take a day trip to Moynak before returning to Tashkent to depart. Moynak was on the shores of the Aral Sea but collapsed after the environmental catastrophe that led to the water’s complete evaporation. The town is a shell of its former self, with countless examples of decaying Soviet-era buildings.

Upon returning to the United States, I will synthesize the sketches, maps, diagrams, and photographs done on site to create a series of analytical drawings documenting the changing urban landscape of Uzbekistan. My research in Uzbekistan will reveal explicit and implicit sites of architectural overlaps in both the buildings and urban fabric of the cities visited. The high resolution analytical drawings and maps will bring the impact of Uzbekistan’s history on its architecture to a broader audience. Uzbekistan has been at the crossroads of history for thousands of years and its architecture will reflect that.